Improving Wildlife Habitat with the Family Forest Carbon Program

For many landowners, spotting a fox, songbird, or other wildlife on their property is one of the highlights of spending time on their land. In fact, 73% of family forest owners in the U.S. say that wildlife is an important reason for owning forestland.1 The good news is that the forestry practices offered by the Family Forest Carbon Program (FFCP) are highly compatible with managing land for wildlife. Let’s look at some examples of management practices you may see in your FFCP forest management plan and how they help create the ideal conditions for certain wildlife species.

Why not just let nature take its course?

For some, forest management is new, unfamiliar, and overwhelming. Not knowing the right thing to do can result in doing nothing at all. Others think that the best thing for the land is to simply leave it alone. However, research shows that sustainable management can often help landowners reach their goals—including improving wildlife habitat.

One reason is that centuries of human intervention suppressing natural occurrences like fires, floods and beaver activity have hindered these natural disturbances that previously encouraged new forest growth and supported certain wildlife species. We can’t change the past, so our best option as forest stewards is to care for the land in a way that accepts and improves this new reality.2

Additionally, because of factors like invasive species, pests and pathogens, natural disasters, and climate change, our nation’s forests and the wildlife within them are under threat even when left untouched by humans. Leaving forestland that is already unhealthy or at risk of these threats to fend for itself could result in further decline in its health and value.

“We didn’t realize for quite a while what a big problem invasive species were. Sometimes you don’t know which is the bad guy and which is the good guy, so you do nothing. I have to admit I spent a lot of years doing nothing when I should have been more active. The Family Forest Carbon Program gave me some real tools, and I felt empowered—like I could do some of these things. It gave me a sense that I have the right resources.” — Kathy McClure, Beaver County, PA

How does removing invasive plants help wildlife?

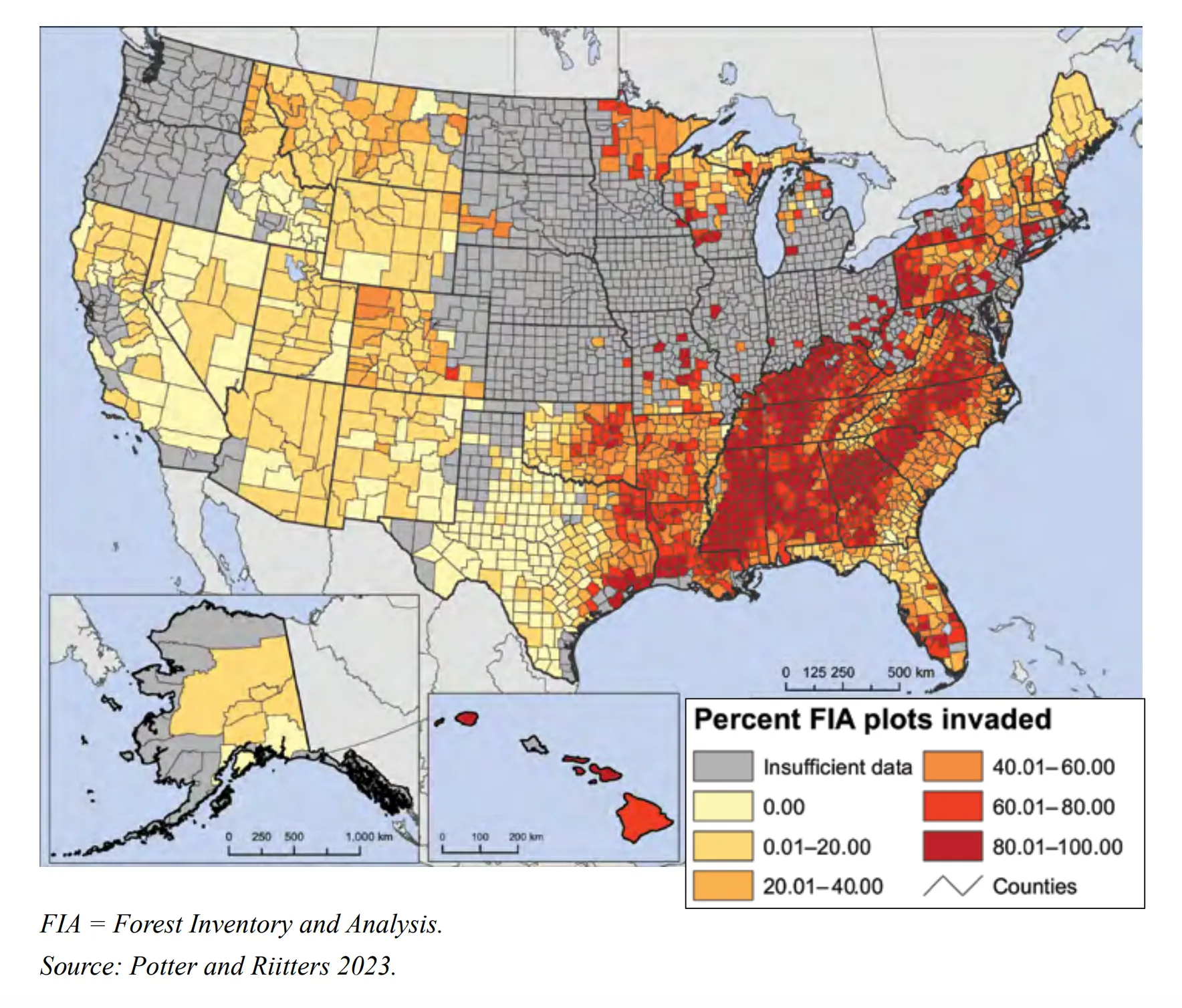

Research shows that forests in the southeastern, northeastern, and upper-midwest states have the highest rates of invasive plant species in the US.3 When left untreated, these species compete with native plants for resources like water, sunlight, and nutrients, introduce new pests and diseases to the ecosystem, and increase the risk of fire. The ripple effect caused by these threats often includes biodiversity loss, habitat fragmentation, and disruptions to nutrient and water cycles—all of which can negatively impact wildlife populations.

Our FFCP foresters are well-versed in invasive species management and ready to incorporate prevention and removal activities into your customized forest management plan.

How does delaying harvesting help wildlife?

Many wildlife species—from cavity-nesting birds to foraging mammals—thrive in the complex layers of old growth forests where large mature trees, gap openings from weather events, and deadwood provide a variety of shelter and food sources. The case study below is just one example of a species that can benefit from longer harvesting cycles.

Case Study: The Wood Thrush

The Wood Thrush, a songbird found across the Eastern half of the United States, is disappearing. With global numbers down 50% since the 1960s, this once healthy population is now considered “near threatened,” in the US, partly due to habitat fragmentation. These ground-feeders prefer large, mature forests with rich soils and minimal “edge exposure”, which helps protect them from predators and parasites.

A wood thrush

Through longer harvesting cycles and selective harvesting, you can maintain larger blocks of older, high-quality deciduous and mixed-species trees on your land, supporting the preferred habitat conditions of species like the Wood Thrush.4

How does leaving dead trees help wildlife?

You may notice that the Family Forest Carbon Program limits the removal of dead or dying trees for firewood or other uses. By leaving snags (dead or dying trees that are still standing) and fallen logs and branches, we are emulating the natural presence of deadwood in the forest that so many species rely on. Decaying wood plays an important role in the forest ecosystem, providing food and habitat for a wide variety of species, from the insects and beetles who live in and feed on it, to birds, amphibians, and mammals who use it for shelter and find their food source within it.5

Saproxylic beetle species like the Longhorn Beetle and Pleasing Fungus Beetle enhance forest health by breaking down deadwood and acting as a food source for other animals. By keeping plenty of deadwood around you’re helping these important species to do their jobs of decomposition, nutrient-cycling, and contributing to the forest food web.6

Additionally, the fungi that break down decaying wood play a vital role in returning nutrients back into the soil and creating the conditions for new seedlings to grow, helping the forest to naturally regenerate. While there is a balance to strike, the presence of deadwood in a forest supports biodiversity and ecosystem health, and therefore an important component of FFCP management practices.7

How can sustainable management treatments help wildlife?

Sustainable management treatments like thinning, patch-cutting, and prescribed burning are sometimes recommended in FFCP forest management plans to help maintain and improve forest health. In addition to promoting regeneration and removing competing vegetation, these activities also support wildlife by creating a range of habitats and conditions that enhance biodiversity. One example of this positive relationship between active management and wildlife can be seen in the Eastern Red Bat.

Case Study: The Eastern Red Bat

An Eastern Red Bat

Bats, a valuable but often underrated species, play a key role in forest ecosystems by controlling insect populations that could otherwise threaten important tree species like oaks and hickories. In fact, a recent study found three times as many insects, and five times more defoliation on the seedlings, in a forest plot where bats were absent, compared to a plot where they were present.8

Some bats, such as the Eastern Red Bat, are shown to prefer roosting and foraging in parts of the forest that have been maintained or regenerated, including those treated with management practices like thinnings and patch-cuts.9 This species offers just one example of wildlife that can not only coexist with, but even benefit from sustainable forest management treatments like the ones that may be recommended in your FFCP management plan.

Photo of a beaver, provided by FFCP landowner Susan Benedict.

FFCP Making An Impact: PA Landowner Susan Benedict

Enrolled landowner Susan Benedict inherited land in Pennsylvania that had previously been clearcut, which resulted in the loss of several wildlife species in the decades that followed. In recent years Susan and her family worked with a forester and the Family Forest Carbon Program to manage for wildlife and are happy to report that several species, including beavers and fishers, have returned to the land as a result.

How do I know what’s best for wildlife on my land?

We hope this article has inspired you to consider an intentional, research-backed approach to managing your forest for wildlife. While some scenarios may call for leaving a forest unmanaged, in many cases a forestry expert can identify opportunities for you to support wildlife by enhancing habitat for the species that are important to you and the health of your woodland. When working with the Family Forest Carbon Program, you’ll discuss these goals with your forester and work together to build appropriate actions in your forest management plan. Our goal is to become your long-term partner in forest health by connecting you with the resources and community you need to help your forest thrive for generations to come. We look forward to partnering with you!

Learn More About FFCP

The Family Forest Carbon Program is currently available to landowners with 30 or more acres of forest in 19 states across the eastern U.S.. Interested in learning more? Click here to read more about FFCP and check your eligibility today: www.familyforestcarbon.org.

FOOTNOTES:

-

Butler, B. J., Caputo, J., Robillard, A. L., Sass, E. M., & Sutherland, C. (2021). One size does not fit all: Relationships between size of family forest holdings and owner attitudes and behaviors [Table 2]. Journal of Forestry, 119(1), 28-44.

-

DeGraaf, R. M., Yamasaki, M., Leak, W. B., & Lester, A. M. (2005). Landowner’s guide to wildlife habitat: Forest management for the New England region (pp. 12–13). Burlington, VT; Hanover, NH: University of Vermont Press and University Press of New England

-

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. (2023). Chapter 5. In Future of America’s Forest and Rangelands: 2020 Resources Planning Act Assessment (p. 27). Gen. Tech. Rep. WO-102.

-

Torrenta, R., Hobson, K. A., Tozer, D. C., & Villard, M.-A. (2022). Losing the edge: Trends in core versus peripheral populations in a declining migratory songbird. Avian Conservation and Ecology, 17(1), Article 28.

-

Tognetti, R., Smith, M., & Panzacchi, P. (Eds.). (2021). Climate-Smart Forestry in Mountain Regions. Springer. pp. 281–282.

-

Warriner, M. D., Nebeker, T. E., Tucker, S. A., & Schiefer, T. L. (2004). Comparison of saproxylic beetle (Coleoptera) assemblages in upland hardwood and bottomland hardwood forests. In M. A. Spetich (Ed.), Upland oak ecology symposium: History, current conditions, and sustainability (pp. 150–151). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station. Gen. Tech. Rep. SRS–73.

-

Tognetti, R., Smith, M., & Panzacchi, P. (Eds.). (2021). Climate-Smart Forestry in Mountain Regions. Springer. pp. 283.

-

Quinn, L. (2022, November 1). Bats protect young trees from insect damage, with three times fewer bugs. College of Agricultural, Consumer & Environmental Sciences, University of Illinois. https://aces.illinois.edu/news/bats-protect-young-trees-insect-damage-three-times-fewer-bugs aces.illinois.edu

-

Beilke, E. A., … (2023). Foliage‑roosting eastern red bats select for features consistent with managed forest: Eastern red bats select managed forest portions, large trees, younger openings, and water. Forest Ecology and Management

Related Articles

December 16, 2025

Family Forest Carbon Program's First Ever Credits Delivered to REI Co-op

Today, REI becomes the first buyer to receive carbon credits from the Family Forest Carbon Program (FFCP), a high-integrity forest carbon project designed for small-acreage landowners.

November 20, 2025

New Film Showcases Carbon Project’s Impact on Family Landowners and Nature

The American Forest Foundation (AFF), a national organization committed to empowering family forest owners to create meaningful conservation impact, announced today the release of a new film that tells the story of the Family Forest Carbon Program (FFCP) and its impact on people and the planet.

November 17, 2025

Forester Spotlight: Molly Hooks

We’re proud to feature Molly Hooks, an FFCP forester who brings deep ecological knowledge and a people-first approach to supporting landowners across Georgia.